Moral Clarity, Enlightened Times, and Oil Diplomacy

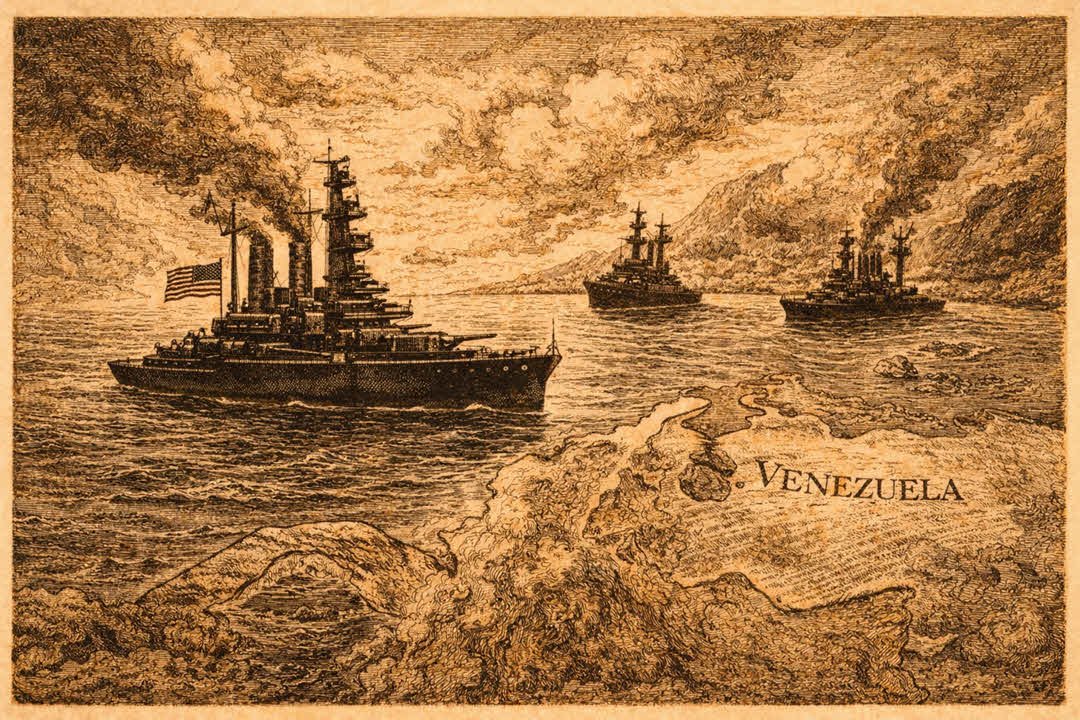

The operation was proclaimed under banners of combating drug trafficking, though this noble aim was curiously paired with the explicit intention of assuming command over the world’s largest petroleum treasure trove. Indeed, one might say that the only thing more abundant in the rhetoric of ‘concern’ for illicit substances was interest and excitement for annual profit sharing with domestic oil magnates.

Thus, it was revealed that the finest oil is not that which springs spontaneously from the earth, but that which is extracted under the auspices of organized liberation. The President of the United States, with delightful and enchanting candor, announced that the nation would now “run the country,” a formulation which, if read literally, suggests no less than total stewardship. This was greeted by its intended audience with the most convenient of explanations: that governance does not require legality, but merely a confident declaration.

Moreover, who among us, after all, has not, in a moment of moral misplacement, desired to run another’s house for them? Were it not for benevolence and kindness, some would maintain, how else could one ensure that a neighbor’s affairs remain consistent with one’s own comfort? Legality, much like courtesy, is an optional accoutrement, easily set aside when one’s interests so demand it.

To be sure, seizing a foreign chief of state presents obvious logistical challenges. But elegant solutions abound. One need only pardon known and convicted drug traffickers of another sort—such as those with unfortunate histories of contraband diplomacy—to preserve a harmonious glow of righteousness. That Venezuela’s contribution to narcotics in America is comparatively minor is but a trivial footnote, for the spectacle of action signals intention far more vividly than any comparative statistic ever could.

It is impossible to exaggerate the strategic brilliance of this performance. For by such means does one simultaneously exhibit global leadership, expand spheres of influence, and invite new debates over international law. The possibility that the United Nations Charter might frown upon such interventions is a charming misunderstanding; for in practice, law is less a constraint than a polite suggestion offered to those who cannot muster the requisite force of conviction.

Critics have noted (with exasperating attention to detail) that such actions may prompt regional realignments, expanded strategic cooperation among rival powers, erosion of credibility in future crises, and, perhaps, even a proliferation of legal challenges in distant tribunals. All of these are, admittedly, potential repercussions if one values what might happen over immediate consequences. Yet one could reasonably argue that no stable order was ever built by patiently waiting for consensus on moral righteousness.

In the end, the operation invites the citizenry to ponder the remarkable convenience of patriotic action: to invade not in fear, but in anticipation; to govern not by delegation, but by assertion; to seek peace through possession. Should the critics wax lyrical about law, justice, or ethical restraint, one might simply advise them to remember that certainty is more satisfying than ambiguity, even if it arrives hand-in-hand with a legion of contradictions.

Thus, we find ourselves in a world where imperial conduct is practiced not in secret, but marketed with all the transparency of a midday fair. None can deny the clarity of its aims: control resources, assert dominance, and redefine legality to suit one’s own ends. It is ‘might makes right’ or perhaps simply ‘the law of the jungle’.

One may call this high noon robbery, foreign policy, or simply the new morality. In any case, it is a spectacle worth observing—preferably from a safe distance, lest one’s own acres become desirable to others whose intentions are equally forthright.