This is not satire . . .

The United States is accurately described as a constitutional federal republic, meaning it’s a system where citizens elect representatives to make laws, but these representatives and the government itself are bound by a supreme Constitution that limits their power and protects individual rights, preventing pure majority rule (a “tyranny of the majority”).

The Fourth Amendment Is Taking Notes from the Eighth Amendment

There was a time when the Fourth Amendment stood upright, alert, and fully conscious. These days, it appears to be lying on a gurney somewhere in federal custody, pulse faint, cause of decline listed as “administrative necessity.”

We are told not to worry. What looks like intimidation is actually “procedure.” What looks like warrantless entry is merely “paperwork.” What looks like a reporter’s home being raided is, in fact, a learning opportunity for journalists who have grown far too comfortable believing the Constitution applies to them.

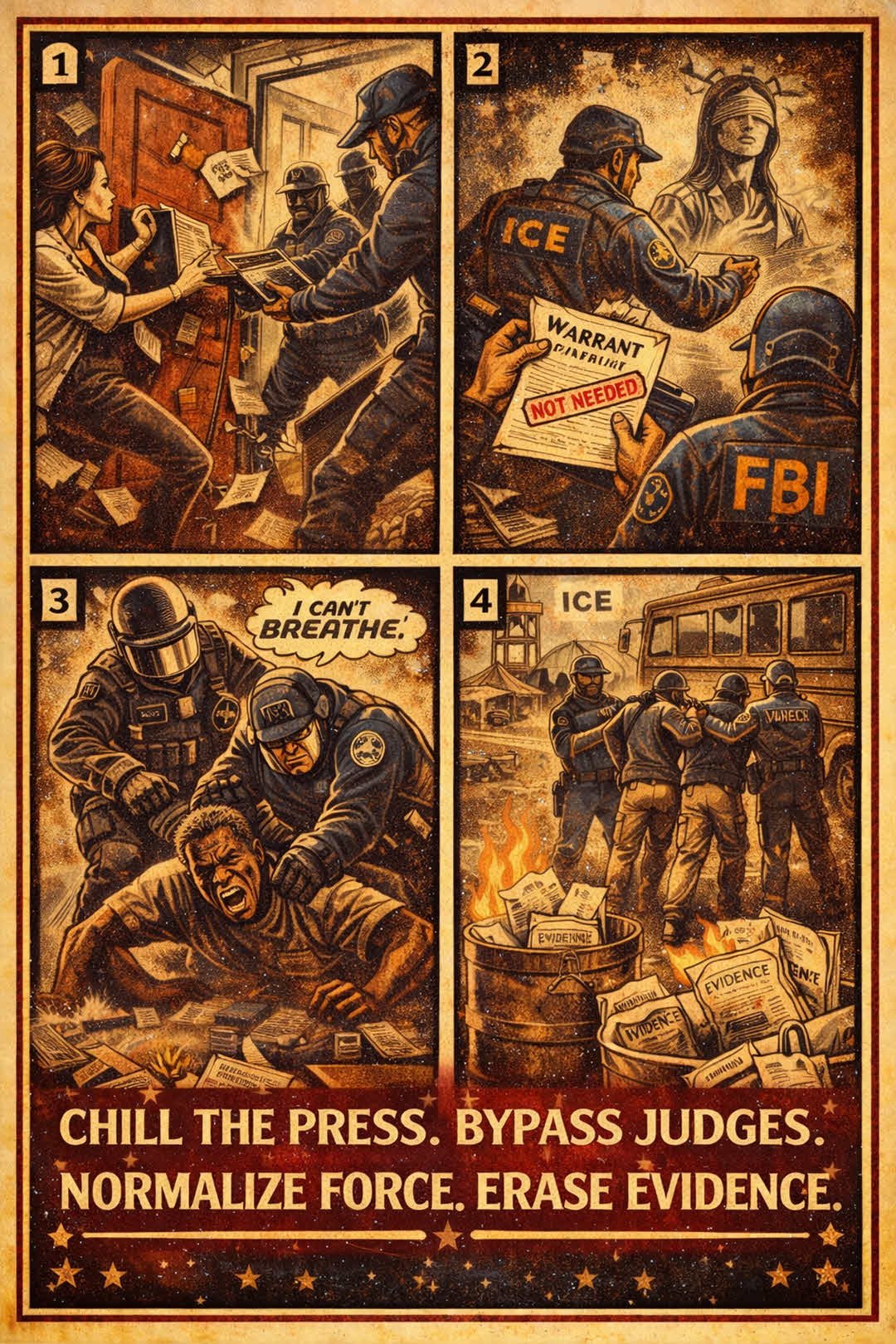

Consider the press raid. A reporter is not accused of a crime, yet federal agents help themselves to her devices, her sources, her professional bloodstream. A judge later says, politely, please do not look at what you already took. This is the legal equivalent of asking a burglar to close his eyes while leaving with the silverware. The lesson for journalists is elegantly simple: your job is protected, unless someone powerful decides it isn’t.

Then there is ICE, the agency that has apparently decided judges are more of a suggestion than a requirement. A secret memo argues that agents may enter homes without judicial warrants, using documents signed by the agency itself. Neutral magistrates, it turns out, slow things down. Constitutional friction is inefficient. Why involve an outside branch of government when you can approve your own invasions in-house and call it governance?

Agents who object are removed. Training materials contradict. The memo is so illegal it can’t be widely shared, which in modern Washington is the surest sign you’re on the cutting edge of executive innovation.

And then there is custody, where all this theoretical power becomes physical. A man dies in a private detention facility, run by a contractor with no experience but ample funding. Cause of death: asphyxiation due to neck and torso compression. “I can’t breathe,” he reportedly said—words that have become so common they may soon be added to the pledge of allegiance. The agency first calls it medical distress, then suicide, then a misunderstanding during a rescue attempt. Witnesses disagree. So, the witnesses are nearly deported.

This is the full cycle: chill the press, bypass judges, normalize force, and then manage the aftermath by removing evidence before it can testify.

We are told this is about enforcement. The public disagrees. Polls show Americans may tolerate strict border policy in theory, but recoil when masked men arrive, without warrants, and sometimes with lethal force. Even voters who want “law and order” can still recognize lawlessness when it wears a badge.

The administration is betting that fear will outlast attention, that fatigue will beat memory, and that the Constitution will eventually stop protesting. But documents don’t forget. Videos don’t forget. And neither will voters when the time comes.

The Fourth Amendment may be in custody—but the public is watching.

Note: Eighth Amendment

The 8th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1791 as part of the Bill of Rights, prohibits the federal government from imposing excessive bail, excessive fines, or cruel and unusual punishments. It limits the severity of penalties for criminal defendants, ensuring punishments are proportionate to the crime and not inhumane.