Notes on Swiftain Satire

First, a story about a wise king.

There once was a kingdom, and in this kingdom, a king ruled with great wisdom. The king was renowned across the realm for his extraordinary governance. His counsel was steady, his judgment sound, and his calm demeanor the envy of neighboring lands. Yet this kingdom possessed a peculiarity: it had only one source of water—a single well in the very center of the village, in the very center of the kingdom. Each day, from bakers to blacksmiths, nobles to shepherds, every citizen drank from this single source of water.

But one night, when there was no moon, a wicked witch crept silently into the village and cast a spell upon the well. It was an enchantment that caused anyone who drank from it to lose their sanity. The next day, the unsuspecting people all drank from the well, all except the king, who was so busy he did not have time.

By day’s end, the entire populace had gone quite mad. And in their madness, they proclaimed, with great certainty, that the king had lost his sanity and must therefore be removed.

Remember, though: the king was truly wise. So that night, he quietly snuck down to the well and drank from it.

And the next morning, the people rejoiced, for the king had regained his sanity.

Swiftian Satire

Swiftian satire rests on an elegant observation: when a society drifts into confusion, the surest way to guide it back toward clarity is to help it see itself—quietly, honestly, and with just enough exaggeration to spark recognition. Jonathan Swift understood this better than most. In an age of political upheaval, religious quarrels, and public anxieties, he discovered that a fable could reach hearts and minds more effectively than any proclamation. His worlds were fantastical, yet the people seemed to find them disarmingly familiar.

Historically, satire has always served this purpose. From ancient storytellers to Enlightenment writers, it has offered citizens a gentle lantern with which to examine their own assumptions. A well-crafted satire does not ridicule to cause harm; it illuminates to instruct. It invites readers to consider that human beings—however earnest—are prone to vanity, misunderstanding, and the occasional theatrical display of certainty. Swift simply magnified these traits so that his readers might recognize the patterns within themselves.

In our contemporary world, the need for such reflection has not diminished. Though our surroundings differ from Swift’s Dublin or London, our tendencies remain remarkably consistent. We still argue loudly over small matters, overlook the larger ones, and adopt the prevailing opinions of the crowd with comforting enthusiasm. We still mistake noise for knowledge and passion for wisdom. And at times, like the villagers who believed their king mad, we declare sanity by repeating what everyone else already believes.

Swiftian satire also recognizes a fundamental truth about public life: people would rather accuse a wise king of madness than admit they’ve all been drinking from a poisoned well. And if the king wishes to survive, he must sometimes take a sip himself. This is not cynicism—it is a wry acknowledgement that societies often demand conformity to collective delusion.

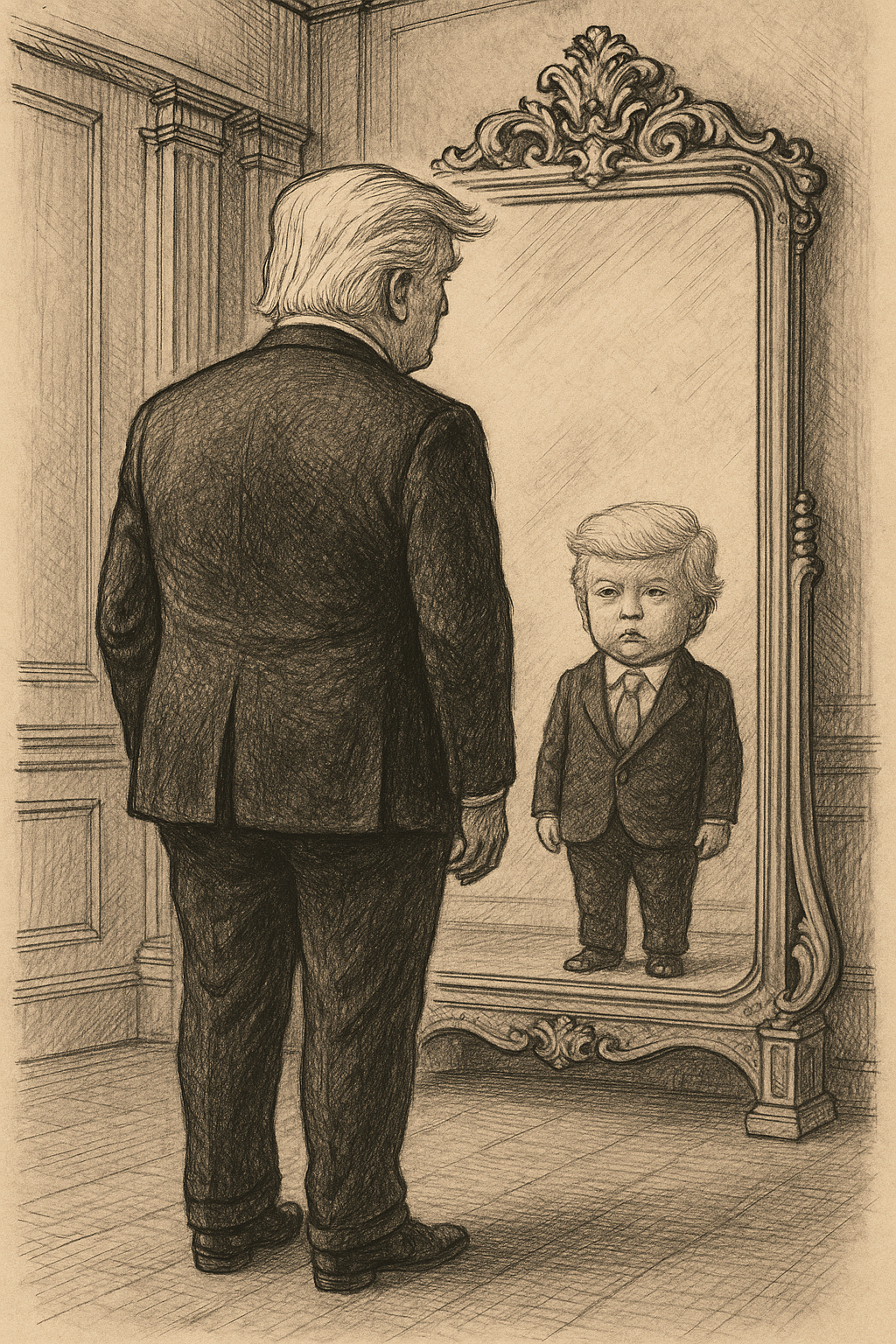

Today’s satirist walks the same path Swift once walked, though the scenery has changed. The task is not to condemn modern life but to place it in a gently distorted mirror—one that reveals familiar habits in new shapes. In this way, satire becomes both historical and contemporary, reminding us that the follies of earlier centuries have not entirely vanished; they have simply learned to dress in modern clothes.

Swiftian satire endures because it offers a quiet reassurance: that by examining ourselves with a touch of humor, we can navigate confusion with greater wisdom. It is an old tradition made new again, inviting us—patiently, and sometimes playfully—to reconsider what we think we already understand.

An Example from the Book

In the grand nursery of public life, Donald Trump often displays the magnificent ego of a particularly determined four-year-old. A four-year-old sometimes believes that stamping one’s foot is a viable negotiating strategy. Like all great toddlers, he insists on winning every game, including those no one else realizes they’re playing. If a tower of blocks falls, it was the blocks’ fault. If another child builds a taller tower, that child is clearly cheating, or the game was rigged.

Adoration, of course, is his. No one can challenge this and be right. A toddler does not merely desire applause; he demands it! Adoration is a universal truth. Thus, every crowd must clap, every friend must praise, and every mirror must reflect not just his face but also the cosmic certainty of his greatness.

The toddler Trump does not simply crave approval; he presumes it, like snack time or recess.